Destination Des Moines by Way of Colorado Springs and a Rwandan Refugee Camp

In December 2016 three 20-somethings —two males and one female aged 24, 22, and 20 respectively—arrived in the United States along with one 4-year-old son mothered by the youngest. They had been brought here from Rwanda through a legal permanent residency program sponsored by Lutheran Family Services (LFS). This young family had lived, along with one other sister and three other brothers, in a Rwandan refugee camp, their destination after fleeing the Congo during a civil war that robbed them of both parents.

Imagine living in a refugee camp for 18 years, most of their young lives. Nice, the 4-year-old boy born at the camp, had known no other way of life. Imagine the simultaneous excitement and terror they must have experienced when four of them struck the immigration lottery and were allowed to come to the United States. It would mean that their family unit would be broken apart, but like so many other immigrants who left their war-torn or impoverished countries, these three adults and one child intended to come to the United States to find work and/or be educated, in hopes that the rest of the family would eventually get to do the same.

“Immigrants tend to be patient because they live not just days or weeks or months in uncertainty; this family lived the better part of two decades not knowing what would become of their lives after their parents had been killed.”

Thinking back to this particular timeframe in late 2016, right after Donald Trump was elected, the family was worried about arrival in the U.S. because there was a basic understanding that the topic of immigration was a hotly contested issue. They didn’t know how they would be received or what kind of hostility or backlash they would encounter. They heard various accounts from various people, but they focused on the positive accounts from others that had come to the States before them, that life here would be better than it was in the camp. They would have to work hard and be expected to learn English in addition to their Swahili and French.

LFS has the mechanics of the refugee program down to a science with a team of individuals collecting donated goods that are stored in a warehouse facility. Once word hits that a family is arriving, they work with a network of apartments to find a landing spot and volunteers set it up with beds, linens, furniture, and kitchen essentials. The refugees arrive with nothing more than the clothes on their backs and precious paperwork.

The apartment was a small two-bedroom, with one area combined as a kitchenette and living area. Brothers Safi and Clement slept in one bedroom while Rehema and her son Nice slept together in the other. They never had the luxury of pillows, so they don’t use them here. The cinderblock walls were painted white and the carpet threadbare and quite likely original to the building. I’m guessing it was built in the ‘70s. There isn’t a plethora of affordable housing and coming from a refugee camp with little to no privacy, this family was grateful to have solid walls and a roof.

Life in the camp had offered just bare essentials: a daily mix of porridge of some kind, and once a week they were given protein, perhaps chicken. Rehema arrived with a congenital hip problem that would require eventual replacement, but her surgery would be stalled for a year due to poor nutrition. Once she remedied her anemia, the prospect of surgery promised relief from debilitating pain.

Nice enjoying his first Hershey bar

After completion of volunteer training, I was introduced as a cultural mentor to this family that had newly arrived to Colorado Springs, Colorado, where Lutheran Family Services settles 150-175 immigrant families annually. My employer at the time, Colorado College, had created a volunteer program in conjunction with LFS called the Refugee Alliance, pairing students and an occasional adult as cultural mentor teams. We would be assigned for the first crucial six months and then the formal relationship with our paired family would theoretically end. Our team comprised a handful of students who turned out to be inconsistently attentive, along with me and another adult, Aditi, herself an immigrant from India. I resisted the formal role of group leader because I was hoping that the students would want to learn responsibility with real human consequences. Unsurprisingly, the heavy lifting quickly defaulted to Aditi and me. While Aditi spent time mostly with Rehema, teaching her some basic English skills, I spent time with Nice, reading him children’s books and prepping him for kindergarten entry in the fall. We spent time on A, B, C’s, numbers, and identifying objects in English.

Oh well, shirts can be laundered!

To supplement the basic household necessities that LFS provided, I organized a toy and nonperishable food drive with my generous workmates. Books and toys were a real luxury for a kid with no possessions. Whenever I arrived, he was drawn to my purse where I stashed special treats such as Hershey bars. Coming from Africa, the family liked the temperature blistering hot in their apartment, and the Hershey bars melted soon upon arrival. It wasn’t going to be a problem (for them) come summertime when the apartment did not have air conditioning.

Our job as cultural mentors was to help them navigate the ordinary: how to ride the bus, learn about fares and currency, get to the grocery store, shop in the most economical way, find items at second-hand stores, assist with paperwork, look for work, review pay stubs, and plug them in to the community as best we could. They were expected to work; go to school; pay rent, other bills and taxes; and be self-sufficient within just a few short months. Just thinking about the litany of things they needed to accomplish in a short period of time was daunting, but that was their new reality and they took it all in stride.

The family arrived in wintertime, so it was imperative that we find them proper weather-appropriate shoes as one of our first exercises. Over the course of time they accrued other more “luxurious” things, such as bicycles to get around, and a computer tablet that allowed them to communicate with their family in Rwanda.

I shall never forget the first time we went grocery shopping together, an overwhelming kid-in-a-candy-shop state of disbelief. So much choice, so many new and mysterious items, and everything was packaged and clean. Imagine doing this without knowing any English! We had no interpreter; we just muddled through it. Once back at the apartment, I had to literally demonstrate how one would cook spaghetti in a pot of boiling water.

Leading up to hip replacement, Rehema is introduced to a health care social worker, Darlene, who generously invited her to rehabilitate in her one-level home. If I needed a reminder of humanity’s potential for kindness, there it was. Perhaps if I subscribed myself to doing more acts of goodwill for others, I would witness repeated evidence that there are many others who routinely do the same.

In spite of the language barrier, Safi managed to find a job right away at the Broadmoor Resort property where he worked washing dishes. And in spite of Rehema’s hip and back pain, she took a job working at another hotel doing housekeeping. Eventually, after hip surgery, she and Safi worked together at the Broadmoor. They would stagger their schedules so that someone was always home with Rehema’s son. Clement had designs on finding a better-paying job than the minimum wage jobs his siblings had scored, and through some friend or “cousin” in Des Moines found a more lucrative job in a slaughterhouse, but it would mean that he would have to move to Iowa. I visited to say good-bye the day before he departed, and it was emotionally heart-wrenching to witness this unit being broken apart so soon upon arrival. I had already developed such fondness for this seemingly unflappable family.

Immigrants are remarkably resilient. They do what they have to do, and so Clement left his siblings and his new home for a better job in Iowa, and life went on. They kept in touch over What’sApp and vowed to one day be back together.

Shortly after beginning my volunteer work with them, I knew that our relationship would extend beyond the formal six-month expectation. Life here was complicated and I couldn’t envision myself irresponsibly walking away and leaving them to chance. There was so much to learn. Furthermore, we became emotionally connected. I became their surrogate, and they even called me “Mom.” Never having children of my own, I never knew that word could sound so sweet.

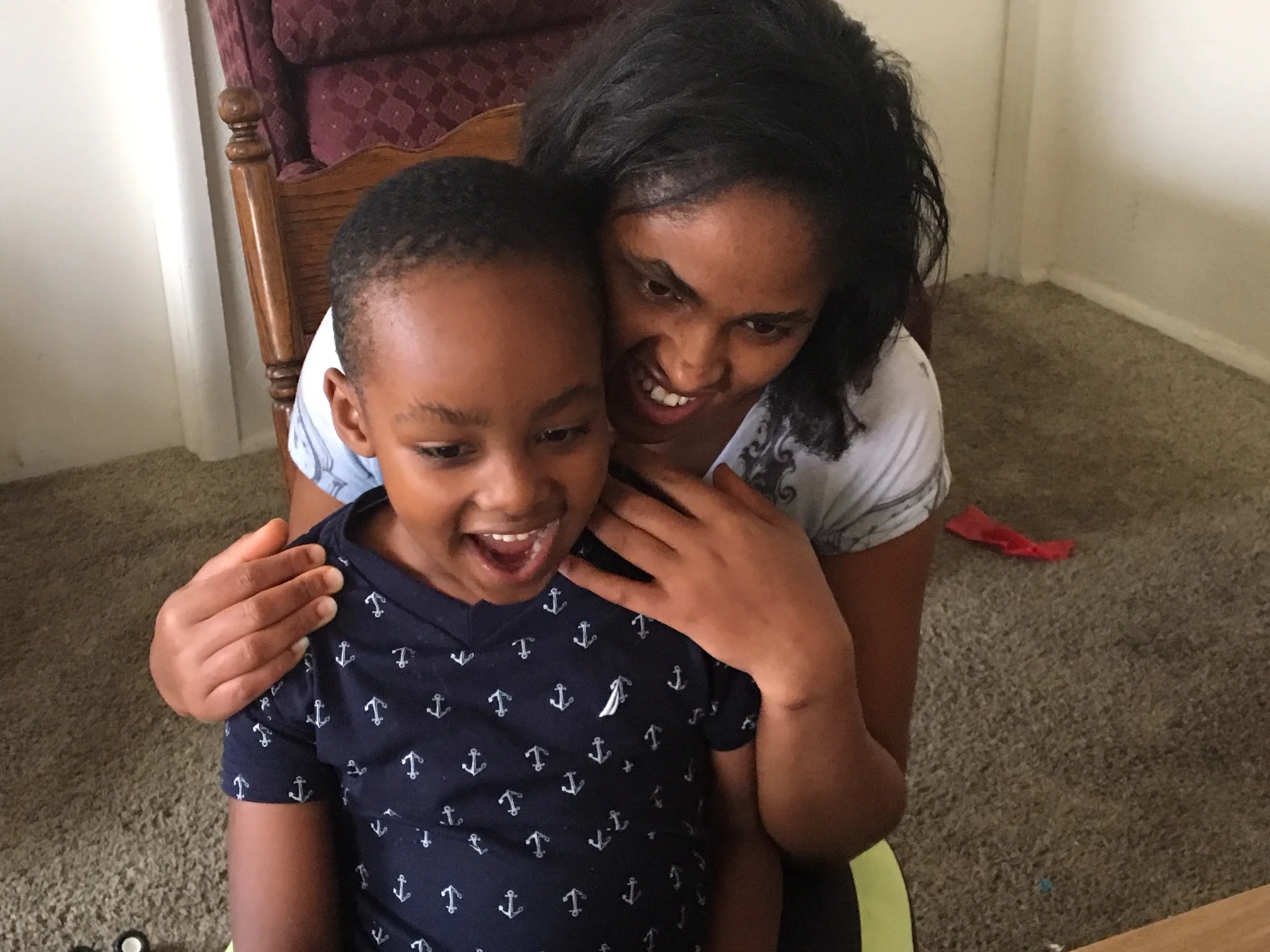

Such excitement! This was the reaction after the first video chat with Daddy left behind in Rwanda.

Though I was a lifeline of sorts, they never burdened me, but they would seek out my assistance whenever they couldn’t figure out something on their own. LFS was available to them, but they had to make it to their office, and without transportation, that required some will and coordination.

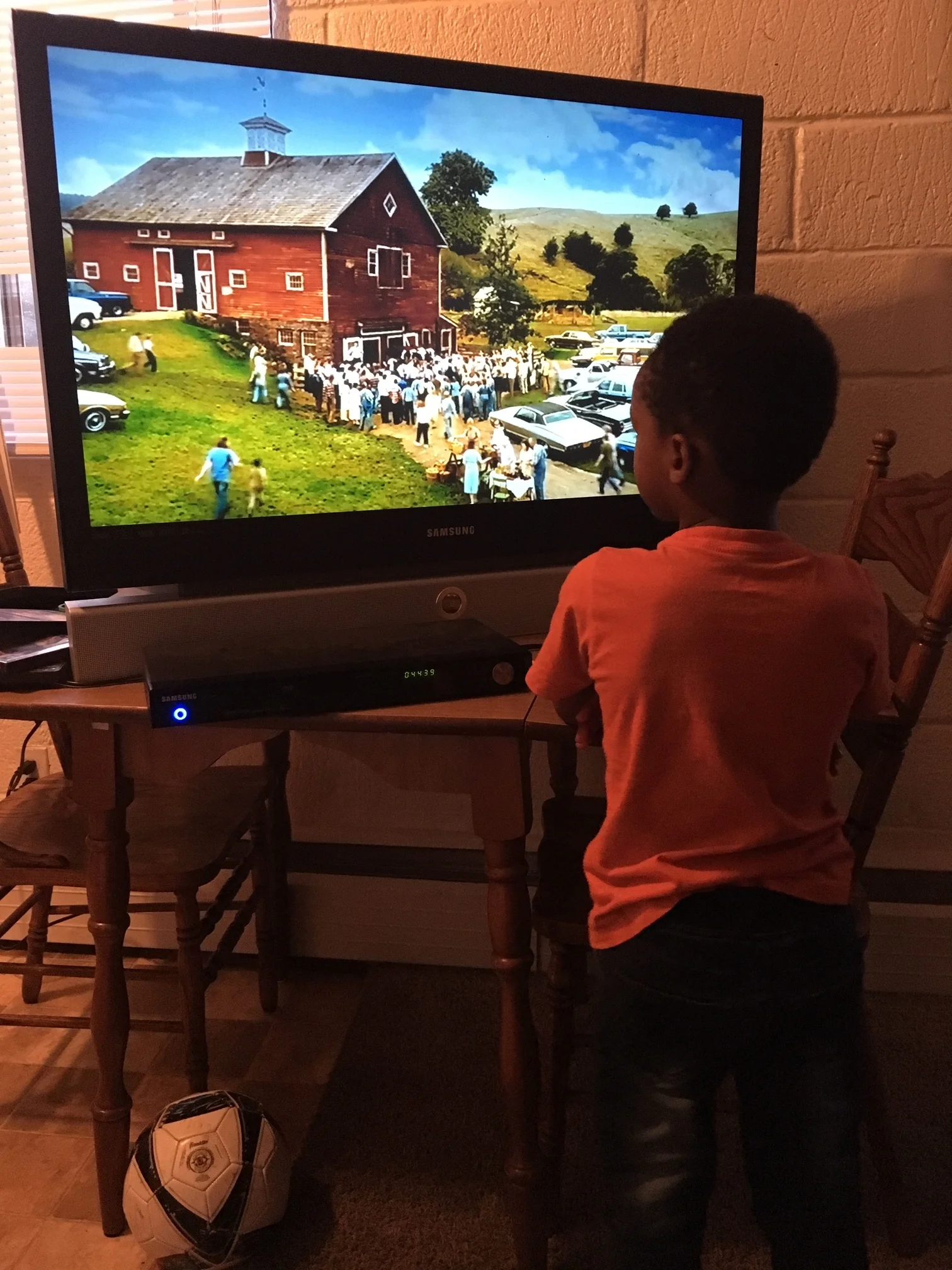

Nice was mesmerized by watching Charlotte’s Web on their first donated TV, which worked only as a monitor for DVD’s but not for very long. Donated goods are rarely pristine, and then the family is left to decipher how to dispose of big items like this in an environmentally friendly way. Often electronic recyclers require a disposal fee, exacerbating the dilemma.

Nice was enrolled in school and would sail through kindergarten and then first grade, and became the family’s conduit to English. He was a sponge; listening to him speak now, there isn’t even a hint of an accent. My spouse Tim and I had given them a small TV, hooked up a window antenna, and set up closed captioning so that words would dance across the screen as they watched programs. The immediate smile on Nice’s face illuminated the room! He was beyond excited to have sound and picture in his otherwise quiet and monotonous apartment. We had tuned the TV to PBS and that’s what was on every time I visited thereafter. Nice didn’t want the adults anywhere near the TV remote, and they kept the peace by leaving it tuned in to his favorite PBS children’s programs.

After Clement left Colorado Springs, Safi grew tired of having to ride a few miles to work on his bike or having to take a circuitous, time-consuming bus route that would also necessitate some walking or awkward boarding of the bike on the bus. Buses don’t necessarily run at convenient times after late shifts or as regularly when he worked on Sundays, which he almost always did.

I didn’t expect the question, or at least not so soon, but he asked if I would teach him how to drive. Never having done this with children of my own, I wondered if I had this particular task in me, but I remembered that my parents started me off in a cemetery where I couldn’t hurt anyone, and so I decided to do something similar. We scouted a parking lot belonging to a nearby arena. When events weren’t taking place, there was an elaborate network of lanes and parking spaces we would have at our disposal. All Safi had to do was avoid the light poles. Undoubtedly it was frightening, but Safi mastered driving in no traffic, so then we set off on quiet side streets. Only twice was I terrified from near misses, but as with anything, the more he practiced, the better he became. This became our routine, going out for driving lessons every chance we had.

Safi behind the wheel

In the two-plus years I’ve spent associated with this family, teaching Safi to drive was my proudest moment so far. It would be truly ordinary if he had grown up here, but within just a few months of arriving, all while working full-time and taking some English classes, this was an extraordinary accomplishment. I was both proud and terrified for him and frankly other people. Driving in Colorado Springs is not easy; it’s a bustling metropolis with three-quarters of a million people in the vicinity, the second largest metro area in the state. Our highways are over-crowded and sometimes filled with fast and aggressive drivers. I didn’t know how this would ultimately play out, but Safi learned enough to obtain his official license and saved up enough to buy a used car, a Jeep. He did not consult me on the purchase, but the car served him well enough (he recently sold it privately and bought a used 2011 Honda Civic hybrid, which I feel much better about). He figured out how to insure and register it with the help of other immigrants. There’s a perpetual handing off of information that gets passed on and on, from immigrant to new immigrant.

Safi is determined to find a higher paying job, for example, as a forklift operator, but that would require getting a GED. While education at the camp had been minimal with a focus on vocational skills, he brought with him a diploma in a properly sealed envelope from the Ministry of Education. Unfortunately, in a moment of paperwork confusion, the sealed envelope was opened, rendering it nearly useless. The diploma, a National Advanced Certificate of Technical Secondary Education A2, indicated that he had received an overall passing grade and it had been stamped with an official seal from the ministry. While it listed all of his completed classes, a grade key equivalent was not provided, so it’s difficult to know exactly the meaning of the scores.

Nonetheless, Safi was worried about having enough time to pursue a GED while working full-time, so he asked if I would help him get his diploma evaluated to see if any of his classes would transfer so that he didn’t have to start from square one. In June of 2018 I began my research to determine which credentialing agency to utilize and immediately found myself in a labyrinth of confusion. There isn’t a single governmental agency tasked with this crucial, consequential work, and reading reviews, the private nonprofit and for-profit organizations that do so aren’t all created equal. I looked at Educational Credential Evaluators (ECE) and SPANTRAN, and after making some initial inquiries that didn’t feel quite right, I decided to go right to the U.S. Department of State and called its affiliated service for a recommendation, the National Association of Credential Evaluation Services. After speaking with a helpful person there, I decided that the World Education Services (WES) organization would be the one I selected.

With Safi’s help, I filled out an elaborate online application on his behalf, mailed a formal request to the Ministry of Education of Rwanda for a sealed diploma, and Safi paid a precious $167 to WES in advance for the evaluation. Nearly one year later, Rwanda has yet to respond to the request. Safi is at a standstill. Twice now I have encouraged him to proceed as if none of his courses would transfer and to keep making progress with his English skills and to proceed with a GED from scratch, if that’s what he ultimately wanted to do.

As I attempted to work through the maze of sequential steps necessary to follow the rules, I became so frustrated. If it was hard for me, I can’t imagine how difficult the process would be for immigrants who just want to do the right thing and earn an honest living. The road is littered with prey organizations out there just to make a buck and take advantage of unsuspecting, earnest people. I rather doubt that there are desired outcomes for evaluating credentials at a secondary education level. I hope the evaluation of post-secondary education is better, but I understand from having talked with numerous under-employed immigrants from all over the world that it’s more often than not a diminishing exchange. While they had been credentialed as physicians and architects and engineers in their native lands, they find themselves on the short end of the stick in the U.S., working instead as building security guards and taxicab and Uber drivers.

After seeing the family fairly regularly, about once a week since they were in such close proximity to my employer, once I stopped working at Colorado College last fall, I unfortunately became preoccupied with other things. Around that same time, three of our family members moved out to Colorado, and we were spending time with family, for the first time living in the same city. I should have seen my adopted family around the holidays, but the holidays came and went. Worse yet, the other adult on the cultural mentoring team had little contact with them after April 2018 because she too had left her job and her family was down to just one car.

Fast forward to early March 2019 when I was surprised to get a text from Rehema indicating that they would be moving on March 23. Thinking they would be moving to a different apartment for some reason, my jaw dropped when I asked Rehema where and she replied, “Iowa cause my siblings came, so we need to be together.” Thus set off a slew of questions and I hopped into gear helping them prepare for a big move and ultimately a joyous reunion. The rest of the family (minus Nice’s father Honore) had made it here from Rwanda around the holidays and settled in Des Moines with Clement. Though everyone preferred Colorado to Iowa (its sunshine, beauty, friendly people), they made the decision to congregate where the highest-paying job was; the cost of living in Iowa would be better too. I assured Safi that his car insurance would be cheaper than Colorado Springs, attempting to focus on the positives.

Their first home, though bare bones with cinderblock walls, provided warm, safe shelter. Not once did I ever hear them complain.

Safi, Rehema, and Nice planned to drive from Colorado Springs to Des Moines in one day and bringing with them only what they could fit in their Honda. They needed help clearing out their apartment, which meant parsing out some items to their friends, giving away most of what they accumulated to Goodwill, and tossing some highly used furniture. I admired Rehema’s resolve to casually let go of what undoubtedly had become precious things to their existence, simply because she had no choice. This is what needed to be done. No time to be sentimental over inanimate things. Eyes on the prize. When they finally pulled away from the apartment, the Honda was packed with the three of them, bare necessity clothes, two copies of the Bible and the Book of Mormon that someone had given to them, the small TV, and a photo that I had taken of the Garden of the Gods in front of Pikes Peak. I wanted them to have a commemorative photograph of the first place they called home as residents of the United States.

The iconic Garden of the Gods in front of America’s Mountain, Pikes Peak

Worried about them driving from Colorado to Iowa, particularly during a time when Nebraska was knee-deep in flood waters, I went to AAA and got them maps and a TripTik with instructions for them to travel through Kansas City rather than Omaha, Nebraska. They didn’t understand why they needed maps when they had come to rely on GPS, but I explained that sometimes GPS can be unreliable, and I didn’t want them to be routed through Nebraska by default because it was a shorter route. I encouraged them to plug in the destination address once they crossed the Kansas line. Not quite sure how it happened or when it happened, but they never made it to Kansas City; they ended up turning north far earlier and going through Omaha anyway. It added at least a couple more unnecessary hours of driving to their already long day, but I was relieved to learn that they made it there safely after all—exhausted but safe.

As of writing time, Nice is finishing out the school year in a brand new school. The siblings who came during the holidays are employed, and Safi and Rehema are once again looking for work. I was able to negotiate all but a $50 (“processing fee”) refund for the education evaluation service that didn’t turn out to be an evaluation at all. Perhaps if we paid off some ministry official in Rwanda, but barring that…

Anticipating a real treat, American burgers and fries

Remarkably, this family has been reunited and knows how to survive as a unit. They love the U.S. and an occasional yummy American burger and fries. They don’t spend money on fast food in order to stretch their dollars and they also are wise enough to know that they don’t want to stretch their waistbands. Their appetites are rather slight after having such limited food supply prior to arrival. Most importantly, they feel safe. They can sleep peacefully at night, and now they can do that as a family unit, not only under the same moon but under the very same roof.

This article is dedicated to my mother, Mary E. Brodowski, who taught me everything I know about being kind and generous to others. She was a model human being to all who knew her and is dearly missed.